American photographer Ralph Gibson has been transforming the world into stark black and white since the swinging 60s. From the soft and sensual to still life, Gibson’s camera has been guided by the decision he made aged only 17 when he knew he was going to become a photographer.

Image copyright

Image copyright

Ralph Gibson

Untitled (San Francisco), 1960

“I just knew my destiny,” says Gibson. “It was like being born rich or smart, a huge gift to know what I wanted.”

Gibson learned his trade in the US Navy before working as an assistant to photographic masters like Dorothea Lange and Robert Frank, both of whom helped shaped the way his photographic eye would develop.

A year into his time with Lange, she invited Gibson, then aged 21, to show her his pictures. As she looked at them she remarked that the problem was he had no point of departure.

Gibson agreed, but then asked: “What is a point of departure?”

Her reply ran counter to the idea of the heroic photographer wandering the streets in search of some kind of truth. Instead she said he had to have an objective and a destination, and then he might intersect with something worth photographing.

Image copyright

Image copyright

Ralph Gibson

Untitled (New York), 1969

“Simply stated,” says Gibson, “this has been the backbone of my career – if there was one quantum leap it was this.”

Yet it was to be some years before he realised this when he published his first book, The Sonnambulist.

In the intervening years, Gibson set out on a career as a photojournalist, eventually joining the prestigious Magnum Photo Agency, though his time there was short.

“I was pursuing the documentary aesthetic,” says Gibson. “I had that look, that approach to the medium but I wasn’t being satisfied.

“I wanted autonomy, all the credit, all the blame,” says Gibson. He did not want to be at the mercy of the newspaper and magazine photo editors, who many photographers felt failed to show off their best frames.

By then he had been working as a photographer for 10 years having started in the navy, aged 17. He met Frank, whose work The Americans has come to be one of the all-time great works of photography. Frank stressed the importance of originality, re-enforcing what Lange had already told him.

Image copyright

Image copyright

Ralph Gibson

Untitled (Hand On Door), The Sonnambulist, 1968

Gibson was staying at the Chelsea Hotel in New York, soaking up the creative vibe, surrounded by artists from many genres, including the musician Leonard Cohen with whom he became friends. An accomplished guitarist, Gibson played guitar on Cohen’s fourth album New Skin for the Old Ceremony.

Returning to room 923 from a trip to Mexico, he pinned the image above, and a few others, on the wall.

“I had an amazing epiphany,” says Gibson. “I felt as though my camera had isolated a bandwidth which we will call a dream reality, it had plugged me into that.

“It was a bit presumptuous, but as my point of departure it was not a bad idea.”

He knew then that this was to be his calling, he ceased all commercial work and set out to create what was to become his first book.

“I don’t know how I survived,” says Gibson. “But I was young and didn’t need much.”

During one weekend he created 36 pictures that formed the basis of The Sonnambulist. It took three years to shoot the rest.

“In that one inspired weekend I was at the same place that the great artists like Picasso or DaVinci go to all day, every day,” says Gibson. “I had accessed that source, a Shangri-La that every artist searches for.”

The Sonnambulist was published in 1970.

“When I made that book I had two of my three Leicas [cameras] at the pawn shop and owed nine months rent on my room at the Chelsea Hotel. But quite by surprise, the book was very well received and so three months later I was established worldwide.”

He soon followed his first book with two more, Deja-Vu and Days at Sea, known as The Black Trilogy.

He had discovered what he calls his “visual signature”.

Some of this he attributes to time spent on the set of Alfred Hitchcock films in Hollywood as a child, while his father worked as an assistant director. The close-ups and the intense light required by the orthochromatic film used at the time subconsciously embedding itself to re-emerge later.

He also attributes some of it to his camera. He sees his Leica as his “Stradivarius” and has no need to constantly upgrade or add new lenses. “This camera is capable of anything I am capable of asking it to do,” says Gibson, spending time refining his mastery of it.

Image copyright

Image copyright

Ralph Gibson

Untitled from Days at Sea, 1974

Image copyright

Image copyright

Ralph Gibson

Untitled from Days at Sea, 1974

Now aged 80 he still feels he is only as good as his next picture and sees the visual literacy that has grown up in recent years around online photo forums as primarily a good thing, although he feels it can lead to work that is repetitive.

“You go on Instagram and you could be looking at a picture by a great photographer or the work of an eight-year-old kid,” says Gibson.

“The software that makes everybody a photographer and gives everybody visual literacy also makes all their photos look the same.

“When taking a photograph with a phone you are letting it find the picture for you, but if you put a rangefinder camera to your eye you are seeing what is in the frame and what is not, you are selecting what to photograph, it is predicated on your vision.

Image copyright

Image copyright

Ralph Gibson

Untitled from Quadrants, 1975

“The upside is that if you look at serious practitioners today at art school, then young people are much more visually sophisticated than I was at the same point.

“I always says your next great masterpiece is only three or four steps away, the question is which direction to go?”

Image copyright

Image copyright

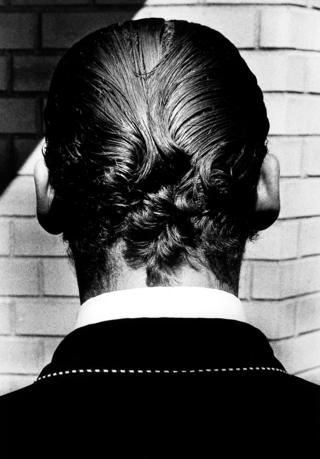

Ralph Gibson

Untitled (Rome), 1988

Image copyright

Image copyright

Ralph Gibson

Mary Jane, Sardinia, 1980

Ralph Gibson’s work can be seen at Photo London until 19 May and at the London Leica Store until 23 June 2019.

All photographs copyright Ralph Gibson.