The most frustrating thing about England in the 1990s was not how bad they often were, it was how good they could be when the handbrake came off. Victories were often achieved in spectacular style, especially against Australia. Although England lost every Ashes series in that decade, they were never whitewashed and usually had a win to cherish. Those victories were particularly precious at the end of a long, draining tour. The glorious turnarounds at Adelaide in 1995 and Melbourne in 1998, both in the fourth Test after the Ashes had been retained by Australia, are usually referred to as “dead-rubber victories”. It’s a slightly unfair label that belittles the Herculean task of winning any Test in Australia.

The yakka was never harder than in Melbourne on 29 December 1998. It was Test cricket’s longest day, with the final session lasting a record four hours and three minutes. England’s Darren Gough and Dean Headley bowled themselves into the ground and into Ashes folklore. “I’d never experienced pressure like it,” says the former wicketkeeper Warren Hegg, who was making his Test debut at the age of 30. “There was an incredible mix of emotion: exhaustion, jubilation, excitement, nervousness. To win at that ground in those circumstances was one of the greatest experiences I’ve ever had.”

England started the match in the kind of disarray that makes Joe Root’s team seem strong and stable by comparison. They were 2-0 down after three Tests and had just been humiliated in Hobart, where Australia A chased a target of 376 in only 55.2 overs. “English cricket,” wrote John Woodcock in the Cricketer, “can never have been in lower water than when Alec Stewart and his team arrived in Melbourne.”

The first day of the Test was washed out and, though England had their moments on days two and three – Stewart punched a memorable first Ashes hundred – they were behind in the game going into the fourth day, thanks mainly to an irksome ninth-wicket partnership of 88 between Steve Waugh and Stuart MacGill.

Waugh had already given Hegg a harsh introduction to Test cricket. “I remember going out to bat in the first innings and I was feeling on top of the world,” he says. “I walked past Steve Waugh, who was at square leg, and he said: ‘You’re an absolute effing embarrassment. You’re in your thirties and you’re just making your debut. You should be embarrassed.’ The only response I could think was a short, sharp: ‘Eff off.’ Then he had me caught at fly slip.”

England started the day on 65 for two, a deficit of five. They lost wickets steadily despite half-centuries from Stewart, his vice-captain, Nasser Hussain, and a fluent Graeme Hick, who thumped 60 from 82 balls. He was the ninth man out, with the lead 151, at which point Alan Mullally, one of the worst batsmen in Test cricket, started slogging an apoplectic Glenn McGrath. “I didn’t take myself seriously with the bat,” said Mullally. “Of course I was shit. But I loved it.” Mullally, who had scored four runs in six innings all series, biffed 16 off 15 balls. McGrath offered some observations regarding the imperfections in Mullally’s technique; Mullally offered to meet him in private for a full and frank exchange of views.

“That was a bit of light relief, because they’d been all over us,” says Hegg. “It gave the Barmy Army something to cheer as well. Mullally was the life and soul of that tour. There’s nothing better than seeing the best bowler in the world being panned round the ground by our No11.”

Mullally’s innings left Australia needing 175 to win. They had a strange problem with small targets, which Stewart highlighted in the England dressing-room, but were cruising at 103 for two when Mark Ramprakash took a staggering diving catch at square leg to dismiss Justin Langer. The catch – and Ramprakash’s angry, strutting celebration – injected a flagging England with the maximum available dosage of energy and belief.

The entire Australia innings took place in the marathon evening session. Headley had already bowled a seven-over spell when he returned to the attack. With the ball starting to reverse, he and Gough – both fast, skiddy and relentless – were an even greater threat. Headley rampaged through the middle order, taking four wickets for four runs in 13 balls, and Australia slipped from 130 for three to 140 for seven.

Waugh, who for England fans stood alongside death and taxes, was still at the crease. He and the debutant Matthew Nicholson inched Australia towards the target; they needed 14 when Waugh claimed the extra half-hour. Headley, whose second spell had been going almost two hours, went to the well one last time to have Nicholson caught behind. “A straightforward wicketkeeper’s catch felt like the best catch in the world,” says Hegg, “because it meant we had another Australia wicket.”

Waugh took a single off the first ball of the next over, putting MacGill on strike against Gough. “There was no better man to have in that situation,” says Hegg. “In Goughie’s mind every ball was a wicket-taking delivery.” The trajectory of Gough’s first delivery to MacGill could not have been better had he drawn it on a graphic. It was a perfect reverse-swinging yorker that thudded into the stumps. Two balls later he nailed McGrath lbw with another yorker. Australia had lost their last seven wickets for 32 and England won by 12 runs. It meant Mullally, the kind of tailender who was too high in the order at No11, had effectively won an Ashes Test with the bat.

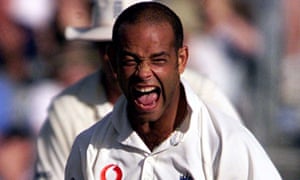

There’s nothing quite like victory to make you lose it, and Gough convulsed with a mixture of anger and joy. “I have never made such a spectacle of myself as I did at that moment,” he said in his autobiography. “I gave it a real King of the Castle pose, very Tarzan, very defiant, stump in hand. After all the stick we’d had to take, I was in no mood to be modest … Sky took great delight in replaying my less than diplomatic mutterings.”

They took greater delight in replaying the wickets that secured a feelgood triumph of the human spirit. Gough and Headley bowled 15.4 and 17 overs respectively to finish with two for 54 and six for 60. Headley’s second spell was an epic: 10-3-26-5. They performed just as well in the next match at Sydney: Gough took a hat-trick, Headley picked up eight in the match, and England might have drawn the series 2-2 but for a questionable third-umpiring decision that reprieved Michael Slater. Instead they lost 3-1.

“Gough was an absolute star against Australia,” said Hussain in his autobiography. “I won’t have a bad word said against him because he was a fantastic, whole-hearted cricketer who loved playing against Australia.” Gough and Headley shared 53 wickets in the five Tests they played together, all against the best team in the world. “He epitomised, to me, what you need to do as a bowler,” said Headley. “Yes, things might not go your way but you never, ever give up on anything.”

Headley could have been talking about himself. “When you looked Deano in the eye, he always wanted to bowl more,” said Hussain. “So many people are not like that.”

Waugh, who scored 152 runs at the MCG without being dismissed, was blamed for Australia’s defeat. His regular policy of trusting tailenders – so successful in the first innings – backfired in the second. Waugh’s despondency at the end delighted Stewart – not out of spite or schadenfreude but because it showed how worthy England’s win was. “I don’t think there’s ever a dead game against Australia,” says Hegg. “They don’t give you an inch, especially someone like Steve Waugh. The jubilation afterwards in the dressing room was incredible. There was such a sense of achievement, to win the historic Boxing Day Test against such a good team.”

When the adrenaline wore off the England team were spent but they forced down a few 4.5% ABV energy drinks at the team hotel with their families and the Barmy Army. The players took turns to stand on a table and sing Oasis songs. “We partied long into the night, I know that,” says Hegg. “They are brilliant, brilliant memories.” It’s also a brilliant precedent for the current team – proving that, no matter how bad things are on an Ashes tour, there is always the chance to take a short cut from rock bottom to cloud nine.